Lucius Caelius Firmianus Lactantius on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

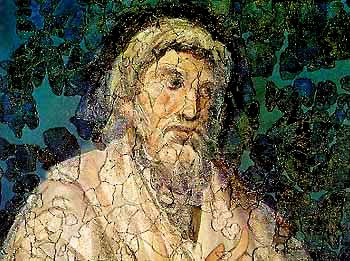

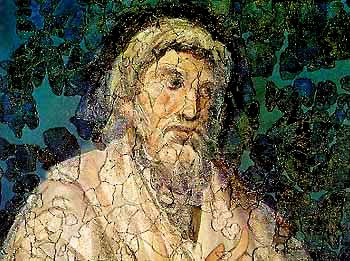

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) was an

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) was an

Like many writers in the first few centuries of the early church, Lactantius took a

Like many writers in the first few centuries of the early church, Lactantius took a

Attempts to determine the time of the End were viewed as in contradiction to Acts 1:7: "It is not for you to know the times or seasons that the Father has established by his own authority," and Mark 13:32: "But of that day or hour, no one knows, neither the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father."

*An ''Epitome'' of the ''Divine institutes'' is a summary treatment of the subject.

*An ''Epitome'' of the ''Divine institutes'' is a summary treatment of the subject.

Lactantius

links to primary texts and secondary sources

Lactantius

text, concordances and frequency list

Bibliography of Lactantius

compiled by Jackson Bryce

Evolution Publishing, Merchantville, NJ , * {{Authority control, state=expanded 3rd-century births 325 deaths 3rd-century Christian theologians 3rd-century Latin writers 3rd-century Romans 4th-century Punic people 4th-century Berber people 4th-century Latin writers 4th-century Romans Ancient Roman writers Berber Christians Berber writers Caecilii Christian apologists Christian writers Christianity in Algeria Church Fathers Converts to Christianity from pagan religions Flat Earth proponents Post–Silver Age Latin writers Tunisian writers Tunisian religious leaders Tunisian Christians

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) was an

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) was an early Christian

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish d ...

author who became an advisor to Roman emperor, Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son Crispus

Flavius Julius Crispus (; 300 – 326) was the eldest son of the Roman emperor Constantine I, as well as his junior colleague ( ''caesar'') from March 317 until his execution by his father in 326. The grandson of the ''augustus'' Constantius I ...

. His most important work is the ''Institutiones Divinae

''Institutiones Divinae'' (, ; ''The Divine Institutes'') is the name of a theological work by the Christian Roman philosopher Lactantius, written between AD 303 and 311.

Contents

Arguably the most important of Lactantius's works, the ''Divin ...

'' ("The Divine Institutes"), an apologetic

Apologetics (from Greek , "speaking in defense") is the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse. Early Christian writers (c. 120–220) who defended their beliefs against critics and ...

treatise intended to establish the reasonableness and truth of Christianity to pagan critics.

He is best known for his apologetic works, widely read during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

by humanists

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanis ...

, who called Lactantius the "Christian Cicero". Also often attributed to Lactantius is the poem '' The Phoenix'', which is based on the myth of the phoenix

Phoenix most often refers to:

* Phoenix (mythology), a legendary bird from ancient Greek folklore

* Phoenix, Arizona, a city in the United States

Phoenix may also refer to:

Mythology

Greek mythological figures

* Phoenix (son of Amyntor), a ...

from Egypt and Arabia. Though the poem is not clearly Christian in its motifs, modern scholars have found some literary evidence in the text to suggest the author had a Christian interpretation of the eastern myth as a symbol of resurrection.

Biography

Lactantius was of Punic orBerber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

origin, born into a pagan family. He was a pupil of Arnobius

Arnobius (died c. 330) was an early Christian apologist of Berber origin during the reign of Diocletian (284–305).

According to Jerome's ''Chronicle,'' Arnobius, before his conversion, was a distinguished Numidian rhetorician at Sicca Vener ...

who taught at Sicca Veneria

El Kef ( ar, الكاف '), also known as ''Le Kef'', is a city in northwestern Tunisia. It serves as the capital of the Kef Governorate.

El Kef is situated to the west of Tunis and some east of the border between Algeria and Tunisia. It has ...

, an important city in Numidia

Numidia ( Berber: ''Inumiden''; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunis ...

(corresponding to today's city of El Kef

El Kef ( ar, الكاف '), also known as ''Le Kef'', is a city in northwestern Tunisia. It serves as the capital of the Kef Governorate.

El Kef is situated to the west of Tunis and some east of the border between Algeria and Tunisia. It has a ...

in Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

). In his early life, he taught rhetoric in his native town, which may have been Cirta

Cirta, also known by various other names in antiquity, was the ancient Berber and Roman settlement which later became Constantine, Algeria.

Cirta was the capital city of the Berber kingdom of Numidia; its strategically important port city w ...

in Numidia, where an inscription mentions a certain "L. Caecilius Firmianus".

Lactantius had a successful public career at first. At the request of the Roman emperor Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

, he became an official professor of rhetoric in Nicomedia

Nicomedia (; el, Νικομήδεια, ''Nikomedeia''; modern İzmit) was an ancient Greek city located in what is now Turkey. In 286, Nicomedia became the eastern and most senior capital city of the Roman Empire (chosen by the emperor Diocletia ...

; the voyage from Africa is described in his poem ''Hodoeporicum'' (now lost). There, he associated in the imperial circle with the administrator and polemicist Sossianus Hierocles

Sossianus Hierocles (fl. 303 AD) was a late Roman aristocrat and office-holder. He served as a ''praeses'' in Syria under Diocletian at some time in the 290s. He was then made ''vicarius'' of some district, perhaps Oriens (the East, including Syri ...

and the pagan philosopher Porphyry; he first met Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

, and Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across the D ...

, whom he cast as villain in the persecutions

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

. Having converted to Christianity, he resigned his post before Diocletian's purging of Christians from his immediate staff and before the publication of Diocletian's first "Edict against the Christians" (February 24, 303).

As a Latin ''rhetor'' in a Greek city, he subsequently lived in poverty according to Saint Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is comm ...

and eked out a living by writing until Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

became his patron

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

. The persecution forced him to leave Nicomedia, perhaps re-locating to North Africa. The emperor Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

appointed the elderly Lactantius Latin tutor to his son Crispus

Flavius Julius Crispus (; 300 – 326) was the eldest son of the Roman emperor Constantine I, as well as his junior colleague ( ''caesar'') from March 317 until his execution by his father in 326. The grandson of the ''augustus'' Constantius I ...

in 309-310 who was probably 10-15 years old at the time.Barnes, Timothy, Constantine: Dynasty, Religion and Power in the Later Roman Empire, 2011, p. 177-8. Lactantius followed Crispus to Trier

Trier ( , ; lb, Tréier ), formerly known in English as Trèves ( ;) and Triers (see also names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle in Germany. It lies in a valley between low vine-covered hills of red sandstone in the ...

in 317, when Crispus was made Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caes ...

(lesser co-emperor) and sent to the city. Crispus was put to death by order of his father Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

in 326, but when Lactantius died and under what circumstances are unknown.

Works

Like many of the early Christian authors, Lactantius depended on classical models.Saint Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is comm ...

praised his writing style while faulting his ability as a Christian apologist, saying: "Lactantius has a flow of eloquence worthy of Tully: would that he had been as ready to teach our doctrines as to pull down those of others!" Similarly, the early humanists

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanis ...

called him the "Christian Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

" (''Cicero Christianus''). A translator of the ''Divine Institutes

''Institutiones Divinae'' (, ; ''The Divine Institutes'') is the name of a theological work by the Christian Roman philosopher Lactantius, written between AD 303 and 311.

Contents

Arguably the most important of Lactantius's works, the ''Divinae ...

'' wrote: "Lactantius has always held a very high place among the Christian Fathers, not only on account of the subject-matter of his writings, but also on account of the varied erudition, the sweetness of expression, and the grace and elegance of style, by which they are characterized."

Prophetic exegesis

Like many writers in the first few centuries of the early church, Lactantius took a

Like many writers in the first few centuries of the early church, Lactantius took a premillennialist

Premillennialism, in Christian eschatology, is the belief that Jesus will physically return to the Earth (the Second Coming) before the Millennium, a literal thousand-year golden age of peace. Premillennialism is based upon a literal interpret ...

view, holding that the second coming of Christ will precede a millennium or a thousand-year reign of Christ on earth. According to Charles E. Hill, "With Lactantius in the early fourth century we see a determined attempt to revive a more “genuine” form of chiliasm." Lactantius quoted the Sibyl

The sibyls (, singular ) were prophetesses or oracles in Ancient Greece.

The sibyls prophesied at holy sites.

A sibyl at Delphi has been dated to as early as the eleventh century BC by PausaniasPausanias 10.12.1 when he described local traditi ...

s extensively (although the Sibylline Oracles are now considered to be pseudepigrapha

Pseudepigrapha (also anglicized as "pseudepigraph" or "pseudepigraphs") are falsely attributed works, texts whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past.Bauckham, Richard; "Pseu ...

). Book VII of ''The Divine Institutes'' indicates a familiarity with Jewish, Christian, Egyptian and Iranian apocalyptic material.McGinn, Bernard. ''Visions of the End'', Columbia University Press, 1998Attempts to determine the time of the End were viewed as in contradiction to Acts 1:7: "It is not for you to know the times or seasons that the Father has established by his own authority," and Mark 13:32: "But of that day or hour, no one knows, neither the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father."

Apologetics

He wroteapologetic

Apologetics (from Greek , "speaking in defense") is the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse. Early Christian writers (c. 120–220) who defended their beliefs against critics and ...

works explaining Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

in terms that would be palatable to educated people who still practiced the traditional religions of the Empire. He defended Christian beliefs against the criticisms of Hellenistic philosophers. His ''Divinae Institutiones'' ("Divine Institutes") were an early example of a systematic presentation of Christian thought.

*''De opificio Dei'' ("The Works of God"), an apologetic work, written in 303 or 304 during Diocletian's persecution and dedicated to a former pupil, a rich Christian named Demetrianius. The apologetic principles underlying all the works of Lactantius are well set forth in this treatise.

*''Institutiones Divinae

''Institutiones Divinae'' (, ; ''The Divine Institutes'') is the name of a theological work by the Christian Roman philosopher Lactantius, written between AD 303 and 311.

Contents

Arguably the most important of Lactantius's works, the ''Divin ...

'' ("The Divine Institutes"), written between 303 and 311. This is the most important of the writings of Lactantius. It was "one of the first books printed in Italy and the first dated Italian imprint." As an apologetic treatise, it was intended to point out the futility of pagan beliefs and to establish the reasonableness and truth of Christianity as a response to pagan critics. It was also the first attempt at a systematic exposition of Christian theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

in Latin and was planned on a scale sufficiently broad to silence all opponents. Patrick Healy argues that "The strengths and the weakness of Lactantius are nowhere better shown than in his work. The beauty of the style, the choice and aptness of the terminology, cannot hide the author's lack of grasp on Christian principles and his almost utter ignorance of Scripture." Included in this treatise is a quote from the nineteenth of the Odes of Solomon

The Odes of Solomon are a collection of 42 odes attributed to Solomon. The Odes are generally dated to either the first century or to the second century, while a few have suggested a later date. The original language of the Odes is thought to ha ...

, one of only two known texts of the Odes until the early twentieth century. However, his mockery of the idea of a round earth

Spherical Earth or Earth's curvature refers to the approximation of figure of the Earth as a sphere.

The earliest documented mention of the concept dates from around the 5th century BC, when it appears in the writings of Greek philosophers. ...

was criticised by Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

as "childish".

*''De mortibus persecutorum

(''On the Deaths of the Persecutors'') is a hybrid historical and Christian apologetical work by the Roman philosopher Lactantius, written in Latin sometime after AD 316.

Contents

After the monumental Institutiones Divinae, Divine Institutes, t ...

'' ("On the Deaths of the Persecutors") has an apologetic character but given Lactantius's presence at the court of Diocletian in Nicomedia and the court of Constantine in Gaul, it is considered a valuable primary source for the events it records. Lactantius describes the goal of the work as follows: "I relate all those things on the authority of well-informed persons, and I thought it proper to commit them to writing exactly as they happened, lest the memory of events so important should perish, and lest any future historian of the persecutors should corrupt the truth."The point of the work is to describe the deaths of the persecutors of Christians before Lactantius (

Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

, Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavi ...

, Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius ( 201 ADJune 251 AD), sometimes translated as Trajan Decius or Decius, was the emperor of the Roman Empire from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was procla ...

, Valerian, Aurelian

Aurelian ( la, Lucius Domitius Aurelianus; 9 September 214 October 275) was a Roman emperor, who reigned during the Crisis of the Third Century, from 270 to 275. As emperor, he won an unprecedented series of military victories which reunited t ...

) as well as those who were the contemporaries of Lactantius himself: Diocletian, Maximian

Maximian ( la, Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus; c. 250 – c. July 310), nicknamed ''Herculius'', was Roman emperor from 286 to 305. He was ''Caesar'' from 285 to 286, then ''Augustus'' from 286 to 305. He shared the latter title with his ...

, Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across the D ...

, Maximinus and Maxentius

Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius (c. 283 – 28 October 312) was a Roman emperor, who reigned from 306 until his death in 312. Despite ruling in Italy and North Africa, and having the recognition of the Senate in Rome, he was not recognized ...

. This work is taken as a chronicle of the last and greatest of the persecutions in spite of the moral point that each anecdote has been arranged to tell. Here, Lactantius preserves the story of Constantine's vision of the Chi Rho

The Chi Rho (☧, English pronunciation ; also known as ''chrismon'') is one of the earliest forms of Christogram, formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters— chi and rho (ΧΡ)—of the Greek word ( Christos) in such a way t ...

before his conversion

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

to Christianity. The full text is found in only one manuscript, which bears the title ''Lucii Caecilii liber ad Donatum Confessorem de Mortibus Persecutorum''.

*An ''Epitome'' of the ''Divine institutes'' is a summary treatment of the subject.

*An ''Epitome'' of the ''Divine institutes'' is a summary treatment of the subject.

Other

*''De ira Dei'' ("On the Wrath of God" or "On the Anger of God"), directed against theStoics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that th ...

and Epicurean

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by Epi ...

s.

*Widely attributed to Lactantius although it shows only cryptic signs of Christianity, the poem ''The Phoenix'' (''de Ave Phoenice'') tells the story of the death and rebirth of that mythical bird. That poem in turn appears to have been the principal source for the famous Old English poem to which the modern title ''The Phoenix'' is given.

*''Opera'' ("Works") A second edition printed in the monastery at Subiaco, Lazio

Subiaco is a town and ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Rome, in Lazio, central Italy, from Tivoli alongside the river Aniene. It is a tourist and religious resort because of its sacred grotto ( Sacro Speco), in the medieval St Benedi ...

, is still extant. It remained in Italy until the late eighteenth century, when it was known to be in the library of Prince Vincenzo Maria Carafa in Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in ...

. The Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second- ...

in Oxford, England, acquired this volume in 1817.

Later heritage

For unclear reasons, he became considered somewhatheretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

after his death. The Gelasian Decree

The Gelasian Decree ( la, Decretum Gelasianum) is a Latin text traditionally thought to be a Decretal of the prolific Pope Gelasius I, bishop of Rome from 492–496. The work reached its final form in a five-chapter text written by an anonymous sc ...

of the 6th century condemns his work as apocryphal and not to be read. Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

s took a renewed interest in him, more for his elaborately rhetorical Latin style than for his theology. His works were copied in manuscript several times in the 15th century and were first printed in 1465 by the Germans Arnold Pannartz and Konrad Sweynheim

Arnold Pannartz and Conrad Sweynheym were two printers of the 15th century, associated with Johannes Gutenberg and the use of his invention, the mechanical movable-type printing press.

Backgrounds

Arnold Pannartz was, perhaps, a native of Prague ...

at the Abbey of Subiaco. This edition was the first book printed in Italy to have a date of printing, as well as the first use of a Greek alphabet

The Greek alphabet has been used to write the Greek language since the late 9th or early 8th century BCE. It is derived from the earlier Phoenician alphabet, and was the earliest known alphabetic script to have distinct letters for vowels as we ...

font

In metal typesetting, a font is a particular size, weight and style of a typeface. Each font is a matched set of type, with a piece (a "sort") for each glyph. A typeface consists of a range of such fonts that shared an overall design.

In mod ...

anywhere, which was apparently produced in the course of printing, as the early pages leave Greek text blank. It was probably the fourth book ever printed in Italy. A copy of this edition was sold at auction in 2000 for more than $1 million.

See also

*Problem of evil

The problem of evil is the question of how to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering with an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient God.The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,The Problem of Evil, Michael TooleyThe Internet Encyclope ...

References

Sources

*External links

Lactantius

links to primary texts and secondary sources

Lactantius

text, concordances and frequency list

compiled by Jackson Bryce

Evolution Publishing, Merchantville, NJ , * {{Authority control, state=expanded 3rd-century births 325 deaths 3rd-century Christian theologians 3rd-century Latin writers 3rd-century Romans 4th-century Punic people 4th-century Berber people 4th-century Latin writers 4th-century Romans Ancient Roman writers Berber Christians Berber writers Caecilii Christian apologists Christian writers Christianity in Algeria Church Fathers Converts to Christianity from pagan religions Flat Earth proponents Post–Silver Age Latin writers Tunisian writers Tunisian religious leaders Tunisian Christians